Cochineal

INSECT DYES

|

||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

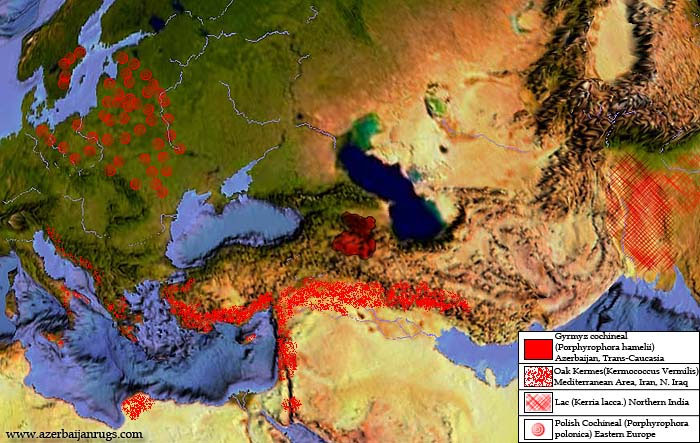

We can summarize all the insect dyes which have been used for rugs into three main groups. These insects are biologically different from each other:

1. Cochineal dye which is isolated from:

a) Porphyrophora hameli - This local type of cochineal has been used in Azerbaijan from ancient times up to the 20th century.

b) Margarodes polonicus and Porphyrophora polonica. - This is called Polish Cochineal. Of the various insect dyes known to readers of oriental decorative art literature, the Polish Cochineal coccid dye insect and its dye are least familiar. However, this coccid dye producer was for many centuries a dominant factor in the textile dye trade and commercial history-of eastern Europe and the Near East. While there is little specific evidence that Polish Cochineal dye was used in any category of Oriental rug, its presence in the market at the time certain rug types were made would be a complicating factor in drawing conclusions about insect dye use.

c) Dactylopius coccus or Coccus Cacti- The cochineal dye which is originated in Spanish America or in other Spanish territories, from a cactus-feeding insect, and was used in certain rugs and textiles of the Caucasus, Persia, and Turkey.

2. Kermes - Kermes (originally kırmız, qırmız ), originates from the word "kirmizi", which means "red" in all Turkic languages. Kermes dye extracted from the dried bodies of the females of a scale insect in the genus Kermes, primarily Kermes ilicis (formerly Coccus ilicis) or Kermes vermilio, distantly related to the cochineal insect, and found on species of oak (esp. Kermes oak) in Mediterranean countries, also in certain parts of Iran.

3. Lac dye -The lac dye originated in Northern India, from an insect (Kerria Lacca), producing both dye and shellac, and was used in rugs and textiles in India and in areas along trade routes where lac was available.

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

Table A. Descriptive Characteristics of Insect Dyes for Oriental Rugs and Textiles |

|

1.1. COCHINEAL OF AZERBAIJAN - KIRMIZ / GIRMIZ (PORPHYROPHORA HAMELI)

|

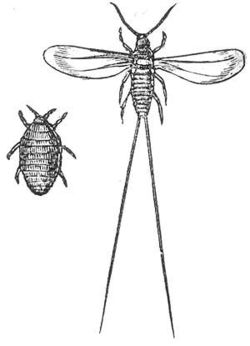

Porphyrophora hameli - Kirmiz (Girmiz) Male and Female (bottom) |

a) Historical References

The earliest historical reference to this dye or color is dated to 714 B.C., when Sargon II of Assyria attacked the kingdom of Urartu* and acquired as part of the booty "scarlet textiles of Ararat and Kurkhi."

A number of references in the Middle Ages to a red of Azerbaijan document a region-specific dyestuff, particularly in the writings of Muslim geographers of the 9th through 14th centuries.

Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Bīrūnī (973-1048 A.D.) and Hamzah Al-Isfahani (d. 961) mentions about the production of insect dye in Azerbaijan.

Ahmad Ibn Yahya al-Baladuri (Balazuri) (d. ca. 892) described Ardizat, to the east of Agridag (Ararat), as Karya-al-Kirmiz, the "town of kirmiz."

According to the 10th century Muslim Arab writer, geographer, and chronicler Mohammed Abul-Kassem ibn Hawqal (born in Nisibis; travelled 943-969 CE), the city of Dabil (Dwn, Dvin, Duvin, Touin) stood north of Ardasat (Ardisat) and was the place where they made "the beautiful color called kermez...(of) a certain worm."

The 14th century famous Azerbaijan geographer and historian Hamdullah Gazvini (1340), mentions the production of girmiz/kirmiz in the plains to the south of Marand, in S. Azerbaijan.

Urartu*- After the fall of the Hittite empire, at the beginning of the first millennium B.C., kingdom of Urartu was formed in eastern Anatolia, which was to survive for 300 years. Urartu, who were closely related to the Hurrians and Hittites in origin.

Sargon II (right), king of Assyria (r. 722 - 705 BC), with the crowned prince, Sennacherib(left)

Abū Rayhān Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Bīrūnī (September 15, 973 in Kath, Khwarezm – December 13, 1048 in Ghazni) was a Muslim polymath of the 11th century, whose experiments and discoveries were as significant and diverse as those of Leonardo da Vinci or Galileo, five hundred years before the them and Renaissance.

b) Cochineal of Azerbaijan - Gırmız (Porphyrophora hamelii): Entomology, Geography, and Biochemistry

Cochineal Red of Azerbaijan rugs was invariably prepared from the coccid species, Porphyrophora hamelii Brandt. Taxonomically, P. hamelii, is a member of the Margarodidae, a family of the super family called Coccoidea (or scale insects). The margarodes spend much of their life burrowing in the ground and feeding on the roots of certain host plants.

All categories of the Coccoidea have quite specific host- parasite relationships. whereby the coccid insect owes its survival and geographic distribution to specific plants.

Cochineal of Azerbaijan - Gırmız insect, P. hamelii, feeds on the roots and lower stems of a number of grasses placed within Aeluropus littoralis. The most often identified host grass is Aeluropus laevis (equivalent to Dactylis littoralis or Poa pungens). This plant is found in the saline marshes along the River Araz, extending to the marshes near Lake Urumia, South Azerbaijan. The flat valley floors around Agridag in Eastern Anatolia is also the common site for the grasses .

.

c) The life cycle and related biological aspects of the Cochineal of Azerbaijan - Gırmız

As with all these dye insects, it is the female which produces the colorant. The insects are collected for dye harvesting during the non- terrestrial mating phase in the early fall. Insect density on the ground and the host grass during this period can be very high. An English translation of the writing of German geographer Friedrich Parrott, ca. 1829, describes "...a number of cochineal insects, some of which were creeping about on the dry sand and short grass, but the greater part were collected...in large nests, round the roots of a short, hard species of grass - the dactylis littoralis...." Parrott was in Caucasia when he made these observations.

In September and October, the cochineal of Azerbaijan emerges from the soil very early in the morning and mates. Fertilized females reenter the soil and lay eggs. In the following April and early May, larvae emerge from the eggs and leave the soil briefly to feed on the new grass. They return to the soil and attach themselves to the roots of the host grass for the balance of the feeding cycle. The dye-bearing female cochineal adult insects are gathered at the time of mating in the autumn.

d) Chemistry & Biochemistry of Gırmız Dyestuff

Methods for the isolation and purification of the dye from the cochienal coccid have still not been fully duplicated from the centuries-old fragments of archival data. We do know a fair amount about the insect's biochemistry, however. In terms of economics and trade, we know that there was a single annual harvest of the adult female in the autumn and that the dye amounts to up to 5% of the insect's live weight. Also, isolation of the dye is complicated by interferences from a rather high fat content, up to about 30% by weight.

The range of colors in the dye extraction media was a simple function of the chemical conditions of the dye harvesting process, while the appearance of the dried cochineal insects themselves could range considerably. In Babenko's article, reprinted here, the director of the laboratory investigating the cochineal of Azerbaijan -girmiz noted that the dried insects were not red but were a variety of other colors. This remark is of marginal relevance to the technology of the dye. Any dye/chemical technologist would confirm that the biochemical form of a dye or pigment in the insect as well as the visual appearance of the insect itself need not accord to the eye with the chemically isolated, pure dyestuff. Linguistically, the various oriental languages which use the root term for worm in various words for red could also intend for this term to connote "red (of the) worm."

What is the chief chemical principle of the dyestuff in the cochineal of Azerbaijan? The answer to this question was not to be found in the open scientific literature, although the related research results of Dr. H. Jonathon Banks for the closely related Polish Cochineal dye product showed that carminic acid was virtually the entire active color principle. Only traces of other colored substances were found.

Identification of carminic acid as the color principle in the cochineal of Azerbaijan, the same as that in the American (Spanish) cactus cochineal and the related Polish Cochineal, may help explain why the Azerbaijan species ceased being a dominant trade material in western Asia. This is discussed further in the report.

e) Use of cochineal in Decorative Arts of Azerbaijan

We would expect that Caucasian rugs of Azerbaijan made as recently as the 18th century and perhaps later would have used cochineal red from Porphyrophora hamelii. When one carefully reads the comments of F. R. Martin and later writers concerning the vivid scarlet red in that group of rugs called the Dragon carpets, especially the earlier examples produced in the 17th and early 18th centuries in Azerbaijan, there is reason to expect that cochineal of Azerbaijan red was used in the earliest carpets of this group and some of their stylistic ancestors.

There is little hard evidence to indicate that use of the cochineal of Azerbaijan as dyestuff in local rug production ended with any phase-out of this red dye as an exportable trade item. There is a general paucity of evidence at the remote village or town level to show either ending or continuation of Cochineal of Azerbaijan - gırmız use. However, in the September, 1987, issue of the Wright Research Report, Wright furnishes information indicating continued use of the cochineal into the early 20th century. In 1925, A. S. Piralov, author of a 1913 study on rugs, wrote a report on rugmaking in Trans-Caucasus. In the report, he cites observations and statistics of M.G. Reliev to show:

"...cochineal is found in the barren steppes of Ganja province (of Azerbaijan) and in the swamps and salt marshes of the Autonomous Republic of Nakhichevan (part of Azerbaijan) in the Araz valley, where the rural population in peacetime (pre-World War I) collected up to 500 puds (9 tons) a year." In the Wright report, either Piralov or Reliev does confuse what is obviously the cochineal of Azerbaijan with the American (Spanish) cactus coccid, since it is noted that "...Coccus cacti (kyrmyz to the natives) is far superior to madder...cochineal is an extremely precious dye and beyond compare." Note also how the persistence of the term "kyrmyz, qyrmyz" in the native area of the cochineal of Azerbaijan would induce and sustain confusion between the local coccid and the oak kermes coccid insects.

| 1.2) THE POLISH COCHINEAL INSECT AND ITS DYE | ||||||||||||||||

|

Margarodes Polonicus (Polish Cochineal) and Scleranthus perennis (plant)

Of the various insect dyes known to readers of oriental decorative art literature, the Polish Cochineal coccid dye insect and its dye are least familiar. However, this coccid dye producer was for many centuries a dominant factor in the textile dye trade and commercial history-of eastern Europe and the Near East. While there is little specific evidence that Polish Cochineal dye was used in any category of Oriental rug, its presence in the market at the time certain rug types were made would be a complicating factor in drawing conclusions about insect dye use.

Historical Record

Prior to the development of aniline, alizarin and other synthetic dyes, the insect was of great economic importance, although this was declining after the introduction of Mexican cochineal to Europe in the 16th century.

According to Donkin, R.A., the research work of Pfister establishes the earliest documentation for Polish Cochineal dye in textiles, those found in Egypt and Syria, dating to Hellenistic-Roman times. Pfister's work in the 1930's involved tests for distinguishing kermes, madder, and cochineal in textiles of Sassanid and Chinese origin. To this writer, however, either Kirmiz or Polish Cochineal sources were possible.

Ancient Slavs developed a method of obtaining red dye from the larvae of the Polish cochineal.

The Capitularies of Charlemagne, according to Donkin, R.A., have the earliest mention of Polish Cochineal (vermiculo) in the West (812 A.D.). There are a number of citations for the 12th century and later regarding the presence and harvesting of Polish Cochineal in eastern and central Europe, and these are summarized by Donkin, R.A. and Brunello, F..A number of the leading medical botanists and herbalists of the 16th and 17th centuries described the Polish Cochineal insect.

The earliest known scientific study of the Polish cochineal is found in the Herbarz Polski (Polish Herbal) by Marcin of Urzędów (1595), where it was described as "small red seeds" that grow under plant roots, becoming "ripe" in April and from which a little "bug" emerges in June. The first scientific comments by non-Polish authors were written by Segerius (1670) and von Bernitz (1672). In 1731, a Dutch biologist living in Gdańsk, Johann Philipp Breyne, wrote Historia naturalis Cocci Radicum Tinctorii quod polonicum vulgo audit (translated into English during the same century), the first major treatise on the insect, including the results of his research on its physiology and life cycle.In 1934, Polish biologist Antoni Jakubski wrote Czerwiec polski (Polish cochineal), a monograph taking into account both the insect's biology and historical role.

From about 1800 on, Polish Cochineal was mainly employed in eastern Europe, specifically in Poland and the Ukraine, and via trade routes in central and western Asia. A number of travelers in their chronicles of the 19th century refer to the "cochineal" produced in Russia and brought to Kashgar, Kabul, and Herat via Bukhara. This type of cochineal may have relevance to the available data we have regarding the use of two types of "cochineal" in Turkoman tribal rugs and trappings.

|

||

| In the 18th and 19th centuries, the extension of Czarist Russian colonial control to western and central Asia was accompanied by trade development in the Polish Cochineal dye. With the partitions of Poland and Ukraine at the end of the 18th century, vast markets in Russia and Central Asia opened to Polish cochineal, which became an export product again – this time, to the East. In the 19th century, Bukhara (Uzbekistan) became the principal Polish cochineal trading center in Central Asia; from there the dye was shipped to Kashgar (Xinjiang), Kabul and Herat (Afghanistan). Since we know that the dye was used in eastern Europe for wool and silk and later was distributed into Turkoman tribal areas, there is reason to assume that the Polish insect probably accounted for the scarlet red in at least some of the extant rugs of those regions and of this period. | ||

|

||

| The insects were harvested shortly before the female larvae reached maturity, i.e. in late June, usually around Saint John the Baptist's day (June 24), hence the dye's folk name, Saint John's blood. The harvesting process involved uprooting the host plant and picking the female larvae, averaging approximately 10 insects from each plant. In Poland, including present-day Ukraine, and elsewhere in Europe, plantations were operated in order to deal with the high toll on the host plants. The larvae were killed with boiling water or vinegar and then dried in the sun or in an oven, ground, and dissolved in sourdough or in light rye beer called kvass, in order to remove fat. The extract could then be used for dyeing silk, wool, cotton or linen. The dyeing process requires roughly 3-4 oz of dye per pound (180 to 250 g per kilogram) of silk, and one pound of dye to color almost 20 pounds (50 g per kilogram) of wool. |

||

| Biochemistry of the Polish Cochineal Similar to other red dyes obtained from scale insects such as kirmiz red of Azerbaijan and American (Spanish) Cochineal dye, the red coloring is derived from carminic acid with traces of kermesic acid. The Polish cochineal extract's natural carminic acid content is approximately 20%. |

|

||

| History The cochineal dye was used by the Aztec and Maya peoples of Central and North America. Eleven cities conquered by Montezuma in the 15th century paid a yearly tribute of 2000 decorated cotton blankets and 40 bags of cochineal dye each. During the colonial period the production of cochineal (grana fina) grew rapidly. Produced almost exclusively in Oaxaca, Mexico by indigenous producers, cochineal became Mexico's second most valued export after silver. Not long after Cortez's arrival in the New World in 1518, cactus cochineal dye started to be shipped back to Spain. Also during this time, the introduction of sheep to Latin America increased the use of cochineal, as it provided the most intense colour and it set more firmly on woolen garments than on clothes made of materials of pre-Hispanic origin such as cotton, agave fibers and yucca fibers. In the second half of the 16th century, there is abundant evidence that New World cochineal dye was being shipped to Spain and elsewhere. This dye reached Europe through Spanish ports such as Cadiz and Seville. By 1560, available dye exceeded Spain's domestic needs and dye was exported to the rest of Europe, beginning with the Low Countries and with Antwerp as market center. England was importing the American (Spanish) dye by 1558. The dyestuff was consumed throughout Europe and was so highly prized that its price was regularly quoted on the London and Amsterdam Commodity Exchanges. American (Spanish) cochineal dye reached Asia by the 1550s by way of at least four trade routes, which are germane to the dye's potential for use in oriental textiles of high value: 1) from the Levant to Persia, and then to India; 2) from Constantinople and Black Sea ports to Turkey and the Caspian region; 3) directly to India in ships from England; and 4) direct transport from New Spain to Asia via the Philippines. Persia was a recognized market for the Spanish dye from the beginning of the 17th century, based on entries in State Papers for 1617-1621. The workshops of Isfahan are recorded in States Papers of 1625-1629 as having received Spanish dye through Venice and on occasion through Constantinople. Donkin, R.A. refers to State Papers of the period to show that dye traders in Persia resold the cochineal substance in cities of northern India in the early 1600s. After the Mexican War of Independence in 1810–1821, the Mexican monopoly on cochineal came to an end. Large scale production of cochineal emerged especially in Guatemala and the Canary Islands. The demand for cochineal fell sharply with the appearance on the market of alizarin crimson and many other artificial dyes discovered in Europe in the middle of the 19th century, causing a significant financial shock in Spain as a major industry almost ceased to exist. The delicate manual labor required for the breeding of the insect could not compete with the modern methods of the new industry and even less so with the lowering of production costs. The "tuna blood" dye (from the Mexican name for the Opuntia fruit) stopped being used and trade in cochineal almost totally disappeared in the course of the 20th century. The breeding of the cochineal insect has been done mainly for the purposes of maintaining the tradition rather than to satisfy any sort of demand. In recent years it has become commercially valuable again, though most consumers are unaware that the 'artificial colouring' refers to a dye that is derived from an insect, at least for the red that is used within the product. One reason for its popularity is that, unlike many commercial synthetic red dyes, it is not toxic or carcinogenic. |

||

| Biology Cochineal insects are soft-bodied, flat, oval-shaped scale insects. The females, wingless and about 5 mm (0.2 in) long, cluster on cactus pads. They penetrate the cactus with their beak-like mouthparts and feed on its juices, remaining immobile. After mating, the fertilized female increases in size and gives birth to tiny nymphs. The nymphs secrete a waxy white substance over their bodies for protection from water and excessive sun. This substance makes the cochineal insect appear white or grey from the outside, though the body of the insect and its nymphs produces the red pigment, which makes the insides of the insect look dark purple. Adult males can be distinguished from females by their diminutive size and their wings. It is in the nymph stage (also called the crawler stage) that the cochineal disperses. The juveniles move to a feeding spot and produce long wax filaments. Later they move to the edge of the cactus pad where the wind catches the wax filaments and carries the cochineals to a new host. These individuals establish feeding sites on the new host and produce a new generation of cochineals. Male nymphs feed on the cactus until they reach sexual maturity; when they mature they cannot feed at all and live only long enough to fertilize the eggs. They are therefore seldom observed. |

||

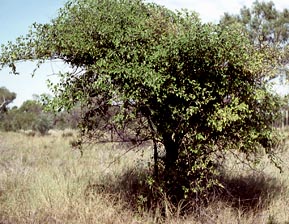

|

Host Plant Dactylopius coccus is native to tropical and subtropical South America and Mexico, where their host cacti grow natively. They have been introduced to Spain, the Canary Islands, Algiers and Australia along with their host cacti. There are 150 species of Opuntia cacti, and while it is possible to cultivate cochineal on almost all of them, the best to use is Opuntia ficus-indica.[9] All of the host plants of cochineal colonies were identified as species of Opuntia including Opuntia amyclaea, O. atropes, O. cantabrigiensis, O. brasilienis, O. ficus-indica, O. fuliginosa, O. jaliscana, O. leucotricha, O. lindheimeri, O. microdasys, O. megacantha, O. pilifera, O. robusta, O. sarca, O. schikendantzii, O. stricta, O. streptacantha, and O. tomentosa. Feeding cochineals can damage the cacti, sometimes killing their host. Cochineals other than D. coccus will feed on many of the same Opuntia species, and it is likely that the wide range of hosts reported for the former species is because of the difficulty in distinguishing it from these other, less common species. |

||

|

|

Farming Cochineals are farmed in the traditional method by planting infected cactus pads or infecting existing cacti with cochineals and harvesting the insects by hand. The controlled method uses small baskets called Zapotec nests placed on host cacti. The baskets contain clean, fertile females which leave the nests and settle on the cactus to await insemination by the males. In both cases the cochineals have to be protected from predators, cold and rain. The complete cycle lasts 3 months during which the cacti are kept at a constant temperature of 27 °C. Once the cochineals have finished the cycle, the new cochineals are ready to begin the cycle again or to be dried for dye production. Dye |

As of 2005, Peru produced 200 tonnes of cochineal dye per year and the Canary Islands produced 20 tonnes per year. Chile and Mexico have also recently begun to export cochineal. France is believed to be the world's largest importer of cochineal; Japan and Italy also import the insect. Much of these imports are processed and reexported to other developed economies

As of 2005, Peru produced 200 tonnes of cochineal dye per year and the Canary Islands produced 20 tonnes per year. Chile and Mexico have also recently begun to export cochineal. France is believed to be the world's largest importer of cochineal; Japan and Italy also import the insect. Much of these imports are processed and reexported to other developed economies

|

of dyeing wool with cochineal

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

What is Lac Composed Of?

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||